I’m a little embarrassed about this. One of the reasons I started this site is because it aggravates me when people over-simplify things or fail to do proper analysis before making claims.

And I just did this myself.

What I Did Wrong

To fully understand where I went wrong, you should probably read Part 2 in my series documenting my DFS journey, “The Book and Addressing the Myths“.

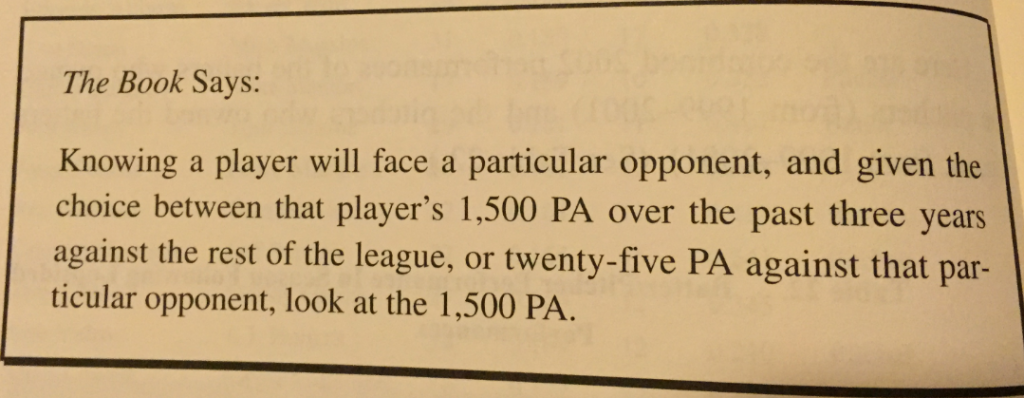

I read The Book. And it’s clear. It’s right there in black and white for all to see. Don’t use BvP to make decisions.

So what’s the problem?

It might help if we first take a step back. When we’re analyzing a particular baseball statistic (pick one), we often find that they’re not predictive from one year to the next. Take batting average for instance. We know that just because a batter hit .300 last year, it’s not a safe bet to count on that repeating itself.

What do we do in this case? We disaggregate the data. We break it down into other component statistics that we can much more reliably project. Instead of looking only at batting average, we’ll start to look at strikeout rate, walk rate, batted ball profiles, historical BABIP, and more.

I Should Have Done This with Batter-Vs-Pitcher Stats

I should have thought to disagreggate things. After all, just like I get along well with certain people and others make me want to drink bleach, some hitters are going to “have an edge” on certain pitchers and they’re going to be overmatched by others.

Not all pitchers are created equal. Not all hitters are created equal.

Whether it’s a batter’s swing path, a pitcher’s arm slot, a batter’s ability to go the other way, a pitcher’s level of deception, a batter’s inability to hit the down-and-in pitch, or a pitcher’s proclivity to throw a changeup in two-strike counts, there are many variables at play in a BvP matchup.

And it is VERY likely that these variables give an edge to the pitcher or the hitter. It’s VERY possible that one of these variables could put the odds overwhelmingly in one party’s favor. It’s also VERY possible that for every factor giving an edge to the hitter that there is an equal and offsetting factor giving an advantage to the pitcher.

It’s not that BvP is useless. It’s not that it has no predictive value. Certain hitters have an edge over specific pitchers. And vice versa. Of course they do. It just makes sense.

The problem is that we don’t know how to separate out the BvP matchups that are predictive those that don’t. Due to small sample sizes, when you go to break it down, BvP matchups probably fall into these nine buckets:

| Bucket | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. | Hitters with an edge over a pitcher, exceeding the expectations due to good luck |

| 2. | Hitters with an edge over a pitcher, performing right at expectations due to neutral luck |

| 3. | Hitters with an edge over a pitcher, underperforming the expectations due to bad luck |

| 4. | Hitter with a neutral matchup against a pitcher, exceeding the expectations due to good luck |

| 5. | Hitters with a neutral matchup against a pitcher, performing right at expectations due to neutral luck |

| 6. | Hitters with a neutral matchup against a pitcher, underperforming the expectations due to bad luck |

| 7. | Hitters overmatched by a pitcher, exceeding the expectations due to good luck |

| 8. | Hitters overmatched by a pitcher, performing right at expectations due to neutral luck |

| 9. | Hitters overmatched by a pitcher, underperforming the expectations due to bad luck |

And just like when you combine a bunch of bright colors of Play Doh into one and end up with brown; when you combine all of these different buckets into one, you end up thinking that batter versus pitcher matchups don’t matter.

How This Came To My Attention

It was an interview with Todd Zola, by Patrick Davitt on the Baseball HQ podcst, and this article at Fantasy Alarm.com that helped me realize the err of my ways.