I recently participated in my The Great Fantasy Baseball Invitational (TGFBI) draft, which, if you’re a Twitter user and follow anyone in the fantasy baseball landscape, you could not have avoided. I do want to share with you some observations I had during the draft, but similar to my other writings, the goal here is to give some actionable advice (even if you’re reading this in the future) and not get too hung up on my team and specific players.

The Context

The invitational is made of 13 separate 15-team leagues. Each of these leagues will compete like any traditional rotisserie league and crown a champion within that league. The twist is that there is also an overall competition across the 13 leagues, whereby all 195 teams are competing in one massive rotisserie competition to crown an overall champion (similar to how the NFBC works). The one person that emerges atop 194 other experts can surely claim to be one of the best fantasy baseball players around.

This is the inaugural year of the competition, but it’s such an innovative idea that there’s no shortage of well-known folks competing. You can see the full list of participants here.

I’m participating in League #13. I happen to be the last name on the roster of the last league! What does that tell you, ha! You can see the draft results here. I was picking from the fifth spot.

My Feelings Going Into the Draft

While I’m obsessed with fantasy baseball, I really don’t view myself as anything special in this arena. Sure, I’ve MacGyver’ed up some neat spreadsheet tools over the years. But I don’t view my preparation process as anything special. I DON’T DO ANYTHING YOU’VE NEVER HEARD OF BEFORE. I’m not holding back any secret tricks of the trade.

And because I don’t do anything special, I was nervous as hell heading into this draft. I joked a few paragraphs back about being the last name on the last league. I don’t really know if that’s indicative of anything, but even if it is, I get it! I don’t even think I’ve written five legitimate articles in the past two years. It wouldn’t surprise me if that’s the lowest output of any participant involved. Meanwhile, many of the others are busting their backs to write articles and create podcasts on an aggressive and regular schedule.

These guys and gals are painstakingly combing over StatCast data, spin rates, hard hit rates, launch angles, swinging strike rates, and more… Meanwhile, I pretty much just let them do the work, read their articles, listen to their podcasts, plop some projections into a spreadsheet, make some manual adjustments, and I’m ready to rock with a comprehensive list of players and expected earnings dollar values.

Imagine my feelings when I’m now competing against some of the folks I admire the most in this business… Mike Gianella, Mike Podhorzer, Jeff Zimmerman, Rudy Gamble, and Rob Silver, to name a few.

Alright. Enough about me. Let’s try to make this useful. I apologize if some of what follows comes across as inflammatory or soap-boxy. Not everything can be sugar-coated. Here are my top lessons learned and observations after participating in this draft.

#1 – Exploit the League Rules

I really, really, really didn’t want to start with this one. It’s what EVERY SINGLE introduction to fantasy sports article ever written in the history of the world has started with.

So you would have expected that every one of the 195 participants would have done this, right?

But guess what??? I’m speculating, but I’d bet less than half of the TGFBI participants gave the rules a worthwhile look (I do realize saying “the TGFBI” is probably redundant, but it looks too weird not to do it). They probably assumed we were playing by prototypical standard rules and just checked to determine if we were using batting average or on-base percentage. But there are two rules we are playing by that are not exactly “standard” and each was something that I think needed to be known going into the draft. These two rules should have affected your behavior in the draft, and possibly in a significant way. Those two rules are:

- Starting rosters include only one catcher but two utility spots

- Rosters allow for five reserves and up to five DL spots for injured players

Why does this matter? In a 15-team league, I show the effect of going from two starting catchers to one as having around a $10 swing in value! That is an ENORMOUS detail (Note: the values in the image reflect the change from 2 C & 1 UTIL to 1 C & 2 UTIL, not just the move to 1 C).

The fact that this change is so significant surprises some people. But these are the same objective calculations that tell me Mike Trout, Trea Turner, Jose Altuve, Chris Sale, Clayton Kershaw, and Max Scherzer should be the highest valued players for the 2018 season. This isn’t speculation or “feel” about how to adjust for position scarcity. If you want to read more about the reason for this, here’s an illustrated example I put together from a few years ago.

As some of the faster drafting leagues started to get into the second and third rounds, we saw the big name catchers start to go. Then word quickly spread over Twitter, “This is a one-catcher league.” The effect quickly kicked in and the catchers starting plummeting. I’m a little disappointed this had to spread like a juicy rumor. I’d have expected everyone to know this going in.

I also suspect that many folks were worried the rules allowed for five reserve spots and no recourse for injured players. I believe this is how NFBC leagues and Fantrax leagues that allow for transactions operate (e.g. NFBC Main Event). I don’t have hard evidence to support this claim, but it just seemed like injured players like Michael Brantley, Michael Conforto, Jimmy Nelson, and Alex Reyes were going later than they should have been. My guess is they’d have been pushed up draft boards aggressively had everyone known this.

Small tip here. I don’t mind pushing up these injured players when you have a realistic way of replacing them that won’t burden you (force you to keep dead weight on your roster). Not only do you secure a talented player at a discount, you get the added benefit of being able to take chances on the waiver wire early in the season, when the odds are higher that you’ll be able to find a hidden gem.

My takeaway here is to not take anything in the rules for granted. Comb over them. Think about what the wrinkles in the rules might allow or incentivize you to do. Tailor your rankings and calculate your dollar values with these rules in mind. And don’t assume your enemies are doing the same. This can be an edge.

#2 – Use Dollar Values Tailored to Those League Rules to Make Decisions

My stance on this is simple and straightforward. If you’re not drafting with a set of projection-based dollar values in mind, you can do better.

I don’t care if you calculate them yourself, if you use the Fangraphs auction value calculator or the Rotowire custom dollar values, or if you buy a piece of software that does it for you… You’re not optimizing your chances of winning if you’re not drafting from values. You need a framework for comparing two hitters to each other, for comparing a hitter to a pitcher, and for making educated decisions. This is what dollar values do! Without dollar values, you’re being subjective. You’re letting biases creep into your decision making.

Do I have evidence that this approach works? The folks at Friends With Fantasy Benefits (specifically @smada_bb) undertook the incredible task of tracking and logging all 13 drafts into a Google Sheet with projected standings and it seems to support what I’m saying.

Overall Projected Top 10 pic.twitter.com/UYz1dMszEH

— smada plays fantasy (@smada_bb) March 16, 2018

I don’t know exactly how every analyst drafts, but based on following folks on Twitter, reading certain sites, and discussions I’ve had with people, I’m pretty certain these folks all do value-based drafting:

- Tanner Bell (@smartfantasybb)- 2nd out of 195 (Whaaaaaaat?)

- Rob Silver (@robsilver) – 3rd out of 195

- Rob Leibowitz (@rob_leibowitz)- 4th out of 195

- Rudy Gamble (@rudygamble)- 9th out of 195

- Jeff Zimmerman (@jeffwzimmerman – 37th out of 195

- Mike Gianella (@mikegianella) – 44th out of 195

I can’t turn this into an enormous research project, but I’d bet large sums of money that many more populating top end of the draft do the same. I will grant you that I’m not searching the second half of the standings for people I suspect to be value-based drafters.

This measure of evaluating a draft is very flawed. I can’t ignore that. Of course the people that draft based upon projections will come out ahead when the evaluation criteria is projections! But I’d argue that projections are our best measure of what we expect to happen this season. So it’s better to be viewed favorably in this exercise than to score low.

NOTE: While still flawed, I do take some solace in the fact that I did not use Steamer or Depth Chart projections in preparing for the draft! I usually use the Depth Chart projections, but for this draft I switched things up and used PECOTA. If I had used Depth Charts and few others did, this method of evaluating my draft would have been extremely biased.

If I can summarize my thoughts, I think too many people make poor decisions in a draft simply because they don’t have a process that allows them to make informed decisions. I couldn’t tell you if a .274-85-20-90-10 hitter A is more valuable than .263-80-27-92-4 hitter B. But a dollar value calculation can! If the difference between player A and B is $1.00 in theoretical value and you have to make similar decisions 28 times in a draft, the cumulative benefit of those decisions adds up!

Listen closely to your favorite baseball podcast. Read fantasy baseball articles a little more closely. If someone’s talking about value, dollars, or earnings, that might be someone to pay a little more closely to when it comes to their player rankings. If, on the other hand, it sounds like they’re shuffling players up and down based on “who they like” or “what they feel”, take that advice with a grain of salt.

#3 – Know the Flaws of Your ADP

A lot has been written about ADP and how to use it properly, so I’ll just mention two nuances worth considering that might be overlooked. Before you use ADP, I think you should understand these things:

- When (over what time period) was it measured?

- Under what league rules are those ADP results for?

When (Over What Time Period) Was ADP Measured?

We live in amazing times. Certain baseball league hosting sites, like the NFBC, have been open for drafting since October 2017. Accordingly, you need to use care when you look at ADP from those sites. The NFBC’s site allows you to adjust the date windows to be included in the calculations.

It would be misleading to use measures dating all the way back to October. We’ve learned a lot and formulated new opinions since then. What happened in an October draft cannot be of value in March. Those early results need to be excluded from your ADP measures. Instead, set the parameters to more recent drafts, like since March 1st or later, for a far better measure of the current mood on players and when they’re likely to be drafted.

Under What League Rules Are ADP Results For?

Take time to consider the league rules the ADP is generated for. Then compare those rules to your own and think how ADP would be affected by those differences.

For example, we know that NFBC drafts utilize two catchers and the TGFBI leagues use one. Looking at March NFBC catcher ADP, 20 catchers are typically drafted in the first 300 picks. Yet in the TGFBI drafts, only 11 had an ADP below 300. This means that by the time the TGFBI drafts got around pick 300, all other players’ ADPs were off by at least those 9 picks. If you thought a lot of the drafters were referencing NFBC ADP, it made sense to start jumping guys one round earlier than what ADP indicated!

I can’t isolate and quantify them, but I think the two UTIL slots in the TGFBI leagues also could have had slight affects on the split between how hitters and pitchers were drafted, how UTIL only players were taken, as well as on how OF were drafted.

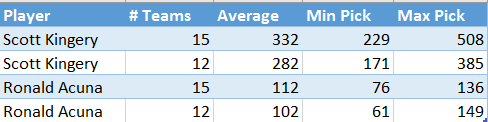

League size can also affect ADP, so if given the chance, be sure to set that parameter when looking at the data. For example, I would be more aggressive on potential impact rookies, like Scott Kingery and Ronald Acuna, in shallower leagues where having viable replacements available can soften the blow if such rookies fail to live up to expectations. A quick review of the NFBC data seems to support this.

Lastly, it’s worth considering that most NFBC drafts are being played in an effort to capture a large overall prize, similar to what I discussed in the TGFBI rules. These folks put up a lot of money. This makes the NFBC ADP reliable. It’s not just a bunch of hacks drafting. But that overall prize does affect behavior. When you’re trying to beat hundreds of other teams and not just the other 14 teams in your league, your behavior changes.

So what makes sense in that environment might not be the optimal play in your home league.

#4 – Think Probabilistically

I think this is the most important tip of the lot, but it’s a deep topic to get into. Books have been written on this (I’d recommend “Superforecasting” by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner) and I’m just trying to squeeze it into a few paragraphs.

The tip here is that projections and isolating a player’s worth into a single projected dollar value is an oversimplification of things. No player has one single projection and one single projected value. What we do not see is that projection is made up of a spectrum of many other projections and the likelihood of each of those projections occurring. You’ve probably heard references to a player’s “90th percentile outcome”. That refers to a what the projection is for when that player is at 90% of their absolute ceiling. More simplistically, what does a stat line for this player look like if everything goes right.

Each of those many projections for an individual player has a likelihood of occurring. Clayton Kershaw could blow out his UCL tomorrow. He could suffer a back injury in June. Or he could make 32 consecutive complete game shutouts. His final projection by a system like Steamer or PECOTA is the weighted average probability of all those outcomes.

I’ll give two examples of how considering the probabilities of different outcomes can help.

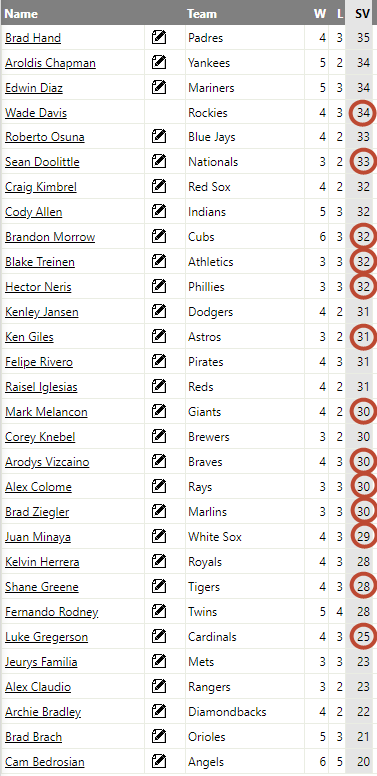

If we know 50% of ALL closers won’t survive, then those that we know have injury, performance, or competition risk should be projected for less than 50% of their team’s saves. I just took a quick spin through the current Fangraphs Depth Chart projections and circled those that I think face higher than average risk of losing their job and for which their projected save total does not seem to reflect.

For example, if you assume a team might be in a position to record 45 saves and you think there is only a 40% chance that the appointed closer makes it through the season in the role, he should be projected for 18 saves (45 * 40%). If you think there is a 30% that the young stud flamethrower takes over, he should be projected for 13-14 saves. And if the aging veteran with closing experience might take over 30% of the time, he too should be projected for 13-14.

The second example I think deserves your attention is the battle for playing time on the Colorado Rockies. Something has to give. Ian Desmond, Gerardo Parra, Carlos Gonzalez, Ryan McMahon, David Dahl, and Raimel Tapia cannot fill three positions simultaneously!

This is where we need to circle back to our understanding of ADP and when it was measured. A lot of ADP was measured before CarGo signed and after Gerardo Parra injured himself earlier in the preseason. This allowed the perception to form that Ian Desmond and David Dahl could patrol the outfield and allow Ryan McMahon to play first base. To further muddy up the situation, there were even reports that Tapia’s speed at the top of the lineup was interesting to the Rockies. Throw CarGo and Parra back into the equation and we have an absolute mess on our hands.

It’s very easy for someone to say, “Don’t worry about playing time. Learn from the Cody Bellinger situation last year. Draft talent. Not playing time.” I hear that from some very smart people, that like to scream “small sample size!” about certain other things, but they want to ignore the probabilities of this situation. They only cite this Bellinger example and ignore the many times that highly talented players have toiled in the minor leagues until July. Those saying this are also quick to say that a player like Dahl or McMahon are just one injury (to Desmond, Blackmon, or CarGo) away from full playing time. But what if it’s Dahl or McMahon that get hurt?!?!

Treating the situation as if only Dahl or McMahon can reap the benefits of an injury is short-sighted, in my opinion. It also seems like everyone assumes these two are guaranteed to be productive as soon as they get their shot to play, when there is a very real probability that these two struggle. Or that Desmond, CarGo, and Parra are highly productive. They have been bona fide major leaguers for many years!

#5 – Think About Your Picks in Groups

On top of getting extremely lucky, I’d peg this as the main reason I had a successful TGFBI draft. I like to always have a plan plotted out of what my upcoming picks will look like. Sometimes it focuses around a specific player, but more often than not it’s just a high level plan of how I’m going to address needs over the next few picks. This is not practical in a fast-paced snake draft, but is ideal in slow draft where you can see the picks leading up to you and have ample time to plan.

This idea isn’t rocket science, but it helps to keep me from panicking and making bad decisions. More importantly, I think it helps squeeze a few extra dollars out of the draft.

This strategy definitely helped me optimize my picks in the middle rounds of this draft. After taking Mookie Betts in the first round, none of my next five picks had a stolen base to their name. So there I sat in the seventh round thinking these things:

- I need A LOT of stolen bases

- I should draft a third baseman. Ten of them are already gone. I don’t want to wait much longer.

- I need another starting pitcher within the next two rounds

- I want another batting average asset so I can cash it in later on a power bat with a terrible average

- I also have to keep pace in power. I didn’t get one of the elite power sources.

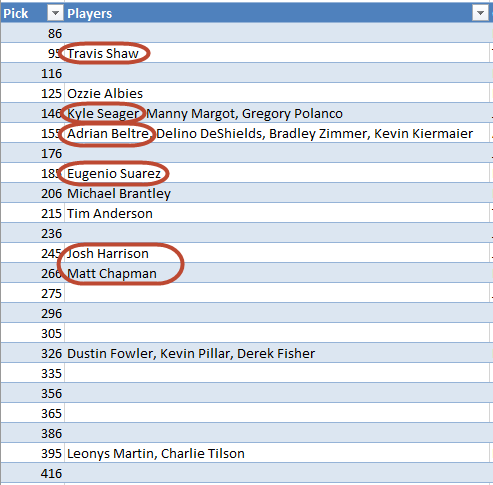

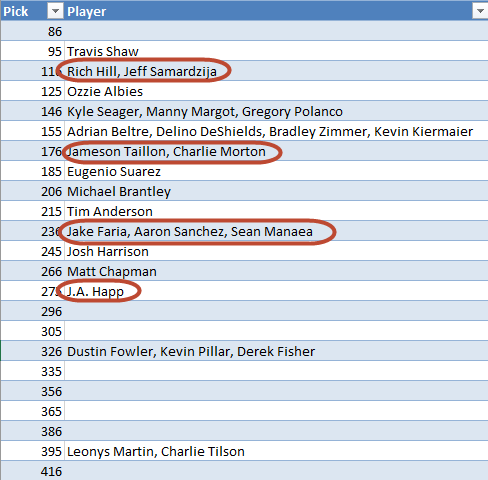

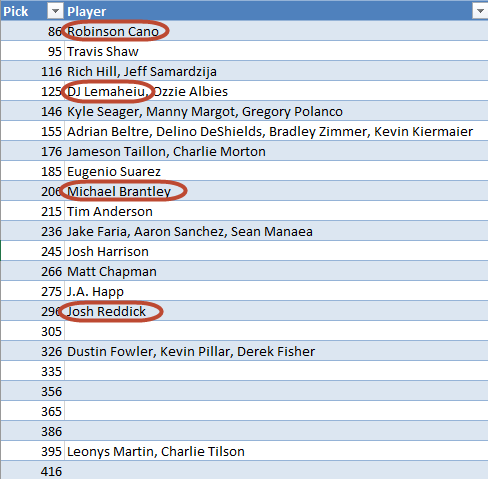

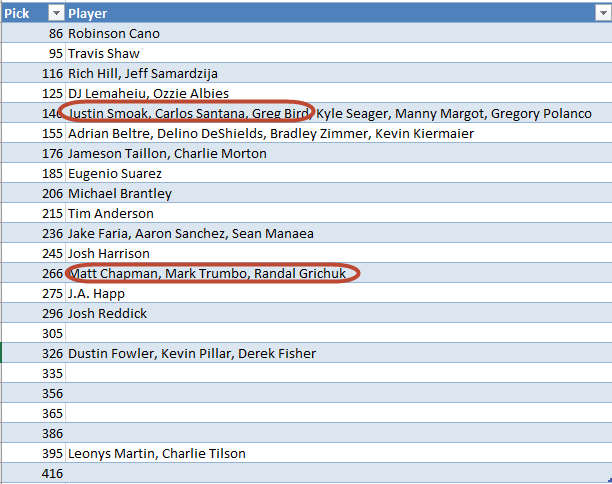

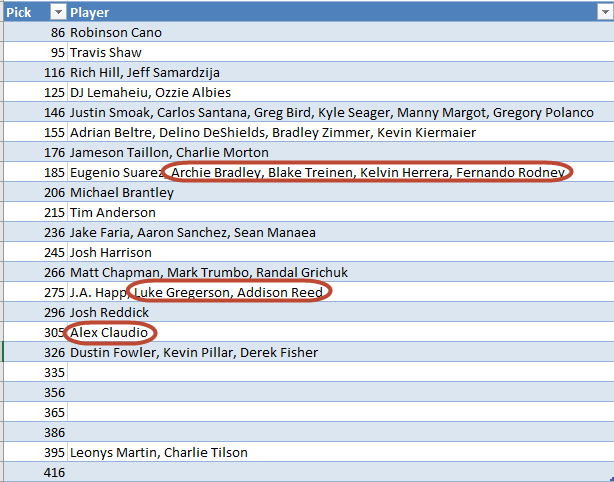

It would be hard to address those needs in only a few rounds, so I take a step back and think about the bigger picture. I mark out potential draft picks that can accomplish these goals and formulate a plan.

I Need A LOT of Stolen Bases

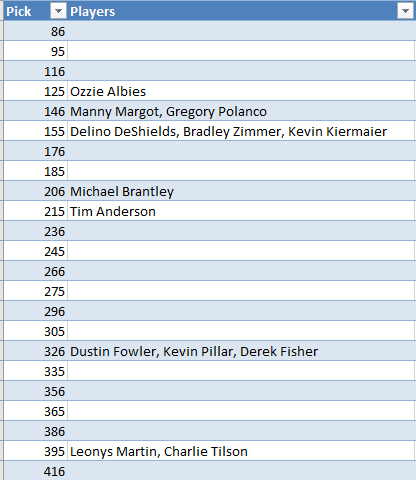

I look at recent NFBC ADP data and add the names of guys that can help me towards this goal. I’m drawn to DeShields and Zimmer because of their high projected steals. They also are drafted right around each other at around 180-190 in ADP. They rate out well above that in my values, so I’m comfortable jumping them two rounds to guarantee I’m not caught with my pants down. I also see another bunch going after 300 that I can target.

I Need a Plan for Third Base

Now I add the 3B that I like to the list. This is flexible and I have to be open-minded here. I never would have anticipated drafting Travis Shaw before the draft (I don’t show him as earning relative to his ADP). But he checks off several needs (power, 10 stolen bases). If I can offset his weaknesses (AVG) with offsetting gains later on, it might be worth the slight loss if it helps me address category needs.

I Need Another Starting Pitcher

With Luis Severino and Jose Quintana in place, this isn’t as pressing of a need as stolen bases and a third baseman. I can work around the SB and 3B on the plan and add in the pitchers I show as having good value.

I Want More Batting Average Assets

I already have a nice base with Betts and Abreu in place. But I know there are guys I really like late that have batting average weaknesses. Further, it’s a very real possibility I won’t take my catcher until the last round, meaning he’s likely to be a liability too.

I add in value guys like Cano, Lemahieu, and Reddick, that I show as likely having strong averages.

I Have to Keep Pace in Power

If I’m going to spend picks on guys like Deshields, Lemaheiu, and Reddick, I know my later picks can’t just be good values, they need to offset the power loss that comes from drafting these guys.

I Can’t Ignore Saves

This is where I think I got lucky in the draft. I came into this with a goal of walking out of the draft with one-and-a-half closers and being willing to chase saves all year. It’s an area I’m comfortable speculating on, whereas I have a hard time buying into hitters that excel in a small sample.

So I add in closers whose prices aren’t too steep.

Fortunately, I was able to snag a closer from each of these groups. I think the three I grabbed, Claudio, Gregerson, and Herrera, are the equivalent of about 1.5 – 2 closers.

Why This Works

By plotting out those players for which I show as earning value, I can be confident in selecting any name on this list. I am also generally able to put at least a couple of similar players down in each group. This gives me confidence that one from that group is likely to be there. My draft strategy is not dependent upon just one player, meaning I don’t need to feel the pressure to make a significant reach.

I also like to imagine what might happen if one was not using an approach like this. It seems like you could easily forget that you have viable power targets available to you many rounds later. You might panic and go for a power bat much earlier than the chart shows. Not only is this not an efficient use of our resources, it could also cause you to miss out on a closer or stolen base specialist because you didn’t have this vision available.

Final Thoughts

I mentioned toward the very beginning of this post that I DON’T DO ANYTHING YOU’VE NEVER HEARD OF BEFORE. I’m pretty certain that’s true. But what this draft illustrated to me is even though many people are aware of these things, NOT MANY WILL ACTUALLY APPLY ALL OF THESE STRATEGIES.

I didn’t outline any ground breaking strategies in this article. But I did show you several different tactics that I think allowed me to squeeze a little bit more value out of my draft. Each strategy allowing a little more value. Each draft pick helping to squeeze a little more juice from the orange. And when you look at all of these little things together, they add up and can make a difference.

Good luck this season! Thanks for reading.

Man, tweeting about catchers in my league being drafted like it’s a 2 catcher league was the biggest mistake of my Twitter career!

That’s right! It was you!

Yes. Did you (and others) forget it was a competition? Or is instant chest-thumping and/or idiot-shaming required to be a pert?

I didn’t actually think people read my tweets or care what I say! Besides, part of being in the industry is doling out advice, and the tweet served as advice – don’t draft catchers in a one catcher league at the same ADP as those in two catcher leagues!

Mark me down as another value based drafter!

Checks that ADP sheet. See you finished 6th of 195. Nods.

I think it’s interesting that we have little overlap in players, or at least inconsequential overlap. Matt Chapman, Luke Gregerson, and Michael Brantley. More than one way to skin a cat.

I’m a little jealous of how you managed to do that while still sprinkling in selective upside picks like Story, Moncada, Musgrove, Richards, and McMahon. I feel like I struggle with that.

Yeah I made a concerted effort to selectively draft upside assets, I figured a value based foundation with a dash of high ceiling was the only way to have a chance at winning the overall